Hygienic applications are bound to the most stringent compliance regulations, a natural expectation considering the importance of maintaining a sanitary environment for processes involving food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Established by different regulatory agencies around the world – including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 3-A Sanitary Standards, Inc., (3-A); and the European Hygienic Engineering And Design Group (EHEDG) – these regulations have proven to help protect the public against the distribution of contaminated products. In addition, these regulations also serve to safeguard manufacturers, providing guideposts that mitigate against catastrophic events such as a product recall or food-borne illness.

As a result of these strict regulations, manufacturers must continuously work to help ensure the equipment they use does not impart any adverse effects at any point in the process. Since pumps are used extensively in hygienic applications, they too must be in compliance with these regulations at all times. This includes complying with cleaning and sanitation procedures that are designed to meet hygienic requirements.

As a result of these strict regulations, manufacturers must continuously work to help ensure the equipment they use does not impart any adverse effects at any point in the process. Since pumps are used extensively in hygienic applications, they too must be in compliance with these regulations at all times. This includes complying with cleaning and sanitation procedures that are designed to meet hygienic requirements.

However, properly cleaning these process pumps doesn’t come without its share of challenges. Opting for a complete pump disassembly is effective, but not efficient and very time-consuming. Another option, which many operators prefer, is the clean-in-place (CIP) method. Yet, this comes with its own set of challenges.

Process pumps in hygienic applications endure a lengthy series of cleaning phases, including at least four for rinsing alone. The typical phases of the CIP process consist of removing gross debris and/or product recovery; pre-rinse; detergent recirculation; intermediate rinse; second detergent recirculation; intermediate rinse; disinfection; and final rinse. While this thorough process is essential, it also creates its share of problems, including inefficient product recovery, excessive CIP flow rates, increased water hammer, and performance issues caused by temperature variations.

The Problems With CIP

The Problems With CIP

Product recovery is the first problem to address before the CIP process begins. The pump, along with any major part of the process installation, is typically full of product. If the pump cannot run dry and provide vacuum and compression effects, then product recovery can’t occur. In this scenario, alternative methods are used, such as a pigging system. While useful at recovering product in specifically designed pipe sections, it is ineffective at removing product from valves, filters and pumps. Another method is water and air flushing, but this is prone to creating product contamination and waste.

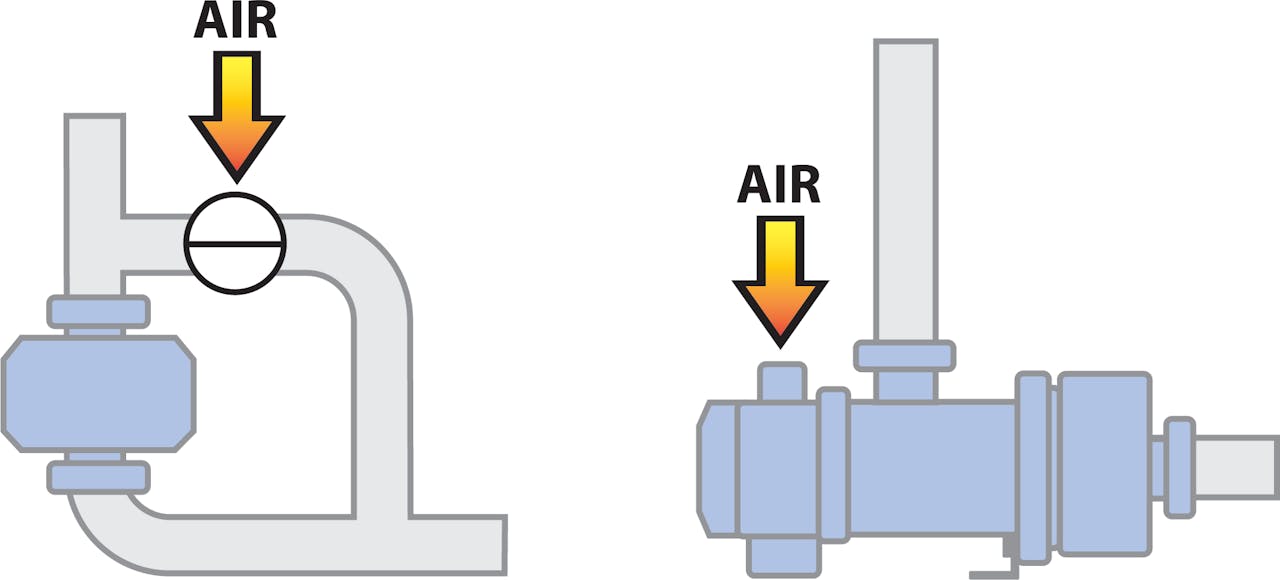

Excessive CIP flow rates present another problem. This rate, determined by in-pipe velocity, is based on a minimum value, usually 1.5 to 3 m/s. To provide effective cleaning, the flow must be turbulent, resulting in a flow rate almost always higher than the process flow rate. Because of this, most process pumps require a bypass to avoid an excessive internal pressure drop during CIP. However, no one has mastered the ability to split the CIP flow rate between the pump and the bypass, meaning there is no guarantee the pump will receive a thorough cleaning.

A third issue comes from water hammer, created when the CIP fluid gains speed before reaching the process in the pump. When the fluid reaches the process, it creates a shock that can severely damage the pump’s mechanical seal and shafts. Ideally, putting the CIP system as close to the process as possible can mitigate this issue, but most systems are found further away.

Lastly, temperature variations are also troublesome. CIP fluid temperature may vary from 20°C (70°F) up to 90°C (200°F). If the pump technology has thin clearances, they must be enlarged to withstand these temperature fluctuations to avoid the pump’s rotating parts galling during the CIP’s hot phases. These enlarged clearances, however, can affect pump performance during certain phases of the process. Additionally, waiting times between the hot and cold CIP phases must occur to avoid pump blockage.

The Eccentric Disc & ECS Solution

These problems, though, can be overcome by selecting a pump technology – such as an eccentric disc – that not only has a pump design that makes it easier to get a thorough clean from the CIP process, but can also integrate the CIP system directly into the pump. This new integrated CIP system, often referred to as an Easy Clean System (ECS), incorporates the bypass into the pump, mitigating the need for an additional power source. The compressed air source and solenoid valve used for the regular CIP bypass can be used to power the ECS.

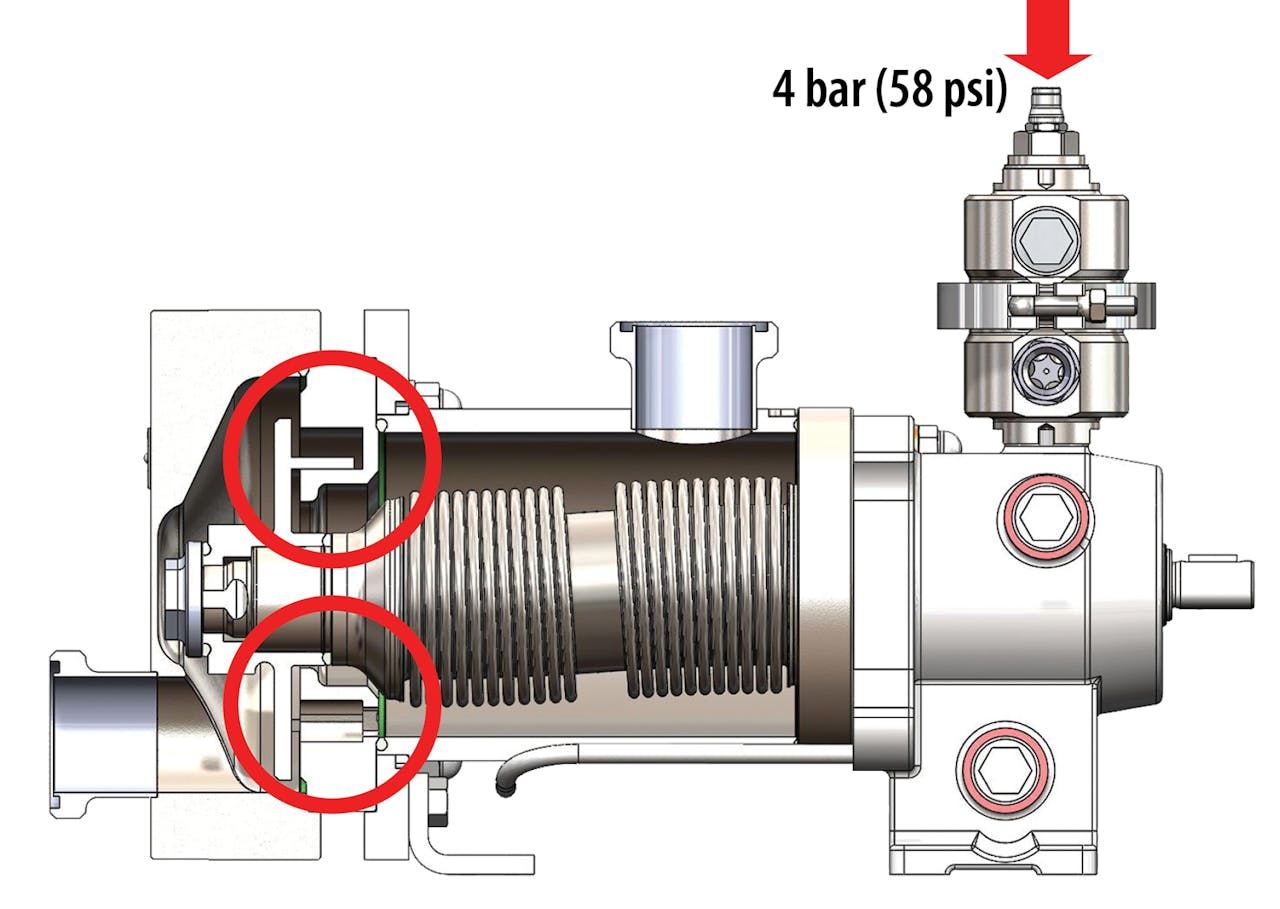

When speaking specifically about eccentric disc pumps, Mouvex offers two pump series that are equipped with an ECS: SLS and H-FLO Series Eccentric Disc Pumps. On these models, the transmission includes a pressurized capacity designed to intake 4 bar (58 psi) of compressor air. The air supply opens the pump interior, allowing the full CIP flow rate to cross through the pump with limited pressure drop. This design does not require an external bypass valve or linked piping.

When speaking specifically about eccentric disc pumps, Mouvex offers two pump series that are equipped with an ECS: SLS and H-FLO Series Eccentric Disc Pumps. On these models, the transmission includes a pressurized capacity designed to intake 4 bar (58 psi) of compressor air. The air supply opens the pump interior, allowing the full CIP flow rate to cross through the pump with limited pressure drop. This design does not require an external bypass valve or linked piping.

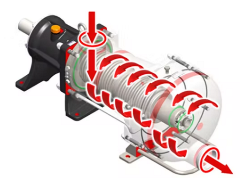

When a pump goes through its usual process, the transmission stays at atmospheric pressure, keeping the disc in contact with the cylinder to allow the pumping action. During the CIP process, the pump stops and compressed air flows through the transmission. The compressed air forces the bellows to stretch and push the disc away from the cylinder, allowing the full CIP flow rate to pass through the pump with limited pressure drop. The compressed air also balances the internal and external pressure of the bellows, creating resistance to pressure and water hammers.

When a pump goes through its usual process, the transmission stays at atmospheric pressure, keeping the disc in contact with the cylinder to allow the pumping action. During the CIP process, the pump stops and compressed air flows through the transmission. The compressed air forces the bellows to stretch and push the disc away from the cylinder, allowing the full CIP flow rate to pass through the pump with limited pressure drop. The compressed air also balances the internal and external pressure of the bellows, creating resistance to pressure and water hammers.

The tandem of eccentric pump technology and an ECS provides an answer to the common problems associated with the CIP process. The eccentric pump design allows it to pump air, which creates a vacuum effect on the pump’s suction side and a compressor effect on the discharge side. This feature results in a plug effect that pushes product out of the pump prior to cleaning and allows some eccentric pumps to recover product from transfer lines at rates of up to 95% (suction) and 85% (discharge). These pumps also help eliminate the risk of additional contamination as the pump uses air already in contact with the product. Additionally, with the ability to remove most of the product before CIP, the pump’s internals are less soiled during the cleaning process and require less detergents and other fluids to reach proper cleanliness.

Because the ECS mitigates the need for the CIP bypass and has the full CIP flow pass through the pump, the cleaning process becomes more thorough and efficient. With the pump fully open, pressure drop decreases dramatically. Additionally, the lack of the CIP bypass simplifies installation and makes cleaning easier overall with less piping, risk and product retention.

Regarding water hammer, the ECS pressurizes the bellows, which provides higher CIP pressure at the pump inlet (up to 6 bar [90 psi]), improving the resistance to this occurrence. On many eccentric disc pumps, the suction port is tangential instead of centered. This offers better cleaning through centrifuge effect and reduces water hammer impact on the bellow.

Regarding water hammer, the ECS pressurizes the bellows, which provides higher CIP pressure at the pump inlet (up to 6 bar [90 psi]), improving the resistance to this occurrence. On many eccentric disc pumps, the suction port is tangential instead of centered. This offers better cleaning through centrifuge effect and reduces water hammer impact on the bellow.

Temperature variations also don’t hamper the functionality of an eccentric pump or the ECS because they don’t need clearances. On many pumping technologies, functional clearances are necessary to prevent pumping parts from galling or clogging. But with eccentric disc technology, those clearances aren’t required because the parts remain in permanent contact. Even with a 90°C (200°F) gap, there isn’t a waiting period between hot and cold phases.

Conclusion

In the hygiene technology landscape, cleanliness will always be a paramount concern and essential to an operation’s success. An ECS-equipped eccentric disc pump can help manufacturers ensure cleanliness while also keeping costs in check and efficiency and functionality high.

Paul Cardon is Business Development Manager PSG Auxerre - FRANCE. He can be reached at (+33 6 88 70 22 90) or paul.cardon@psgdover.com. Mouvex is a product brand of PSG, a Dover company, Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA. PSG is comprised of pump brands, including Abaque, All-Flo, Almatec, Blackmer, Ebsray, em-tec, Griswold, Hydro Systems, Mouvex, Neptune, Quantex, Quattroflow, RedScrew and Wilden. You can find more information on PSG at psgdover.com. Headquartered in Auxerre, France, Mouvex is a manufacturer of positive displacement pumps and compressors for the transfer of liquids in hygienic-manufacturing applications worldwide. For more information on Mouvex, visit mouvex.com.

This article originally appeared on Food Manufacturing.